Open Physics Notes

Physics is the human attempt to listen to the quiet symphony of the cosmos. It is the discipline that asks not merely "what" happens, but "why", and "how", and "under what universal law". To study physics is to trace the logic of the universe, written not in ink or myth, but in mathematics — precise, abstract, and deeply profound.

This journey began long before the word “physics” was coined. In ancient Greece, philosophers such as Thales and **Democritus proposed that nature followed rules — that water or atoms might be the fundamental substance. Aristotle, though deeply flawed in hindsight, constructed an early systematic approach to motion, matter, and the heavens. Yet it would take nearly two thousand years for these ideas to evolve beyond philosophical speculation into measurable, testable science.

That transformation began in earnest during the Scientific Revolution. In the early 17th century, Galileo Galilei turned his telescope to the sky and shattered the geocentric illusion. He saw moons orbiting Jupiter, mountains on the Moon, and stars far more numerous than previously imagined. But Galileo’s deeper revolution lay in his insistence that motion could be described mathematically — that falling objects accelerated in predictable ways, independent of their weight. This insight severed the ancient bond between terrestrial and celestial mechanics and opened the door to a new kind of understanding.

The next step was monumental. In 1687, Isaac Newton published "Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Principia)", in which he articulated the three laws of motion and the law of universal gravitation. Suddenly, the same set of equations could explain an apple falling to Earth and the Moon orbiting the Earth. Newton’s universe was a clockwork of precise and deterministic motion. It could be predicted, modeled, and controlled. The age of classical mechanics had arrived, and it would dominate the next two centuries of scientific thought.

This Newtonian paradigm empowered minds like Leonhard Euler, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, and Pierre-Simon Laplace to generalize mechanics to broader systems, from pendulums to planetary orbits. Laplace, in particular, imagined a universe so deterministic that, given perfect knowledge of initial conditions, the future could be calculated in its entirety. It was an elegant and terrifying vision — a cosmos with no room for chance, mystery, or free will.

And yet, cracks were already forming. The 19th century saw the emergence of thermodynamics, the study of heat, energy, and entropy. Experiments by James Prescott Joule, Sadi Carnot, and Rudolf Clausius revealed that energy was conserved, but its quality degraded. The concept of entropy was born — a measure of disorder that always increased in isolated systems. This irreversibility hinted at a deeper tension within the otherwise time-symmetric laws of mechanics. The arrow of time had appeared.

Simultaneously, Michael Faraday, a self-taught experimental genius, uncovered the invisible structure of electric and magnetic fields. His intuitive grasp of forces acting through space paved the way for James Clerk Maxwell, whose equations unified electricity and magnetism into one electromagnetic field. Published in the 1860s, Maxwell’s equations did more than describe existing phenomena — they predicted that light itself was an electromagnetic wave, traveling through empty space at a constant speed c. This was not just a theory of light; it was a glimpse into a universe where fields, not particles, were fundamental.

But here lay a paradox: Newtonian mechanics assumed time and space were absolute, while Maxwell’s equations implied a preferred frame of reference. To resolve this, scientists hypothesized a luminiferous “aether” through which light propagated. However, in 1887, the Michelson-Morley experiment failed to detect any such aether. Nature, it seemed, cared not for our assumptions.

Enter Albert Einstein. In 1905 — his annus mirabilis — Einstein proposed the special theory of relativity, abolishing the need for aether altogether. He showed that the laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames, and that the speed of light is invariant. Time and space were not separate absolutes, but part of a unified spacetime continuum. In 1915, Einstein expanded his vision into the general theory of relativity, redefining gravity as the curvature of spacetime itself, governed by the distribution of mass and energy. This was not a mere improvement upon Newtonian gravity — it was a radical shift in worldview. Suddenly, space bent, time dilated, and black holes became not science fiction but scientific prediction.

Meanwhile, another revolution was brewing — one even stranger, even more unsettling. Classical physics could not explain why atoms radiated energy in discrete lines, or why the ultraviolet catastrophe didn’t burn the universe. In 1900, Max Planck reluctantly introduced the idea of quantized energy — that light was emitted in discrete packets called quanta. In 1905, Einstein extended this to explain the photoelectric effect, proposing that light behaves not just as a wave, but also as a particle — a photon.

In the 1920s, quantum mechanics erupted into full bloom. Niels Bohr proposed a model of the atom with quantized orbits. Werner Heisenberg developed matrix mechanics, while Erwin Schrödinger introduced wave mechanics. The two formalisms were soon shown to be mathematically equivalent. The famous uncertainty principle emerged, placing fundamental limits on how precisely we can know a particle’s position and momentum. Observation itself seemed to affect reality.

In 1928, Paul Dirac took quantum theory further by incorporating Einstein’s relativity. His Dirac equation not only described the electron, but predicted the existence of its mirror image — the positron — before it was ever observed. Dirac’s work was a triumph of mathematical elegance, and a sign that beauty and truth in physics often walk hand in hand.

And yet quantum mechanics remained deeply weird. The double-slit experiment, quantum tunneling, superposition, entanglement — these phenomena defy classical intuition. Schrödinger’s cat, both dead and alive until observed, became the symbol of this bizarre realm. Is the universe inherently probabilistic? Does observation create reality? These questions remain unresolved, not due to lack of answers, but due to the unsettling nature of the answers we do have.

By mid-century, quantum mechanics and special relativity were united into a new framework: quantum field theory (QFT). Here, particles are not fundamental, but rather excitations of underlying quantum fields. The electromagnetic field yields photons, the electron field yields electrons, and so on. This framework, though abstract, proved astonishingly accurate. Quantum Electrodynamics (QED), developed by Richard Feynman, Julian Schwinger, and SinIchiiro Tomonaga, achieved predictions verified to over 12 decimal places. Feynman’s diagrams made the invisible world of particle interactions visual and calculable.

In time, this approach was extended to other forces. The Standard Model of particle physics emerged — a grand synthesis describing all known particles and interactions (except gravity). It introduced quarks, gluons, W and Z bosons, and the Higgs boson, predicted in the 1960s and finally discovered in 2012 at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. The Standard Model is among the most successful theories in science, yet it is incomplete. It cannot explain dark matter, dark energy, neutrino masses, or gravity itself.

Gravity, that oldest of forces, remains the most elusive at quantum scales. Attempts to merge general relativity and quantum mechanics — through string theory, loop quantum gravity, or other approaches — have yet to succeed. The dream of a theory of everything remains, tantalizingly, just out of reach.

At the cosmological scale, Big Bang theory, cosmic inflation, and observations of cosmic microwave background radiation have revealed that the universe had a beginning — a singularity from which space, time, matter, and energy emerged. The discovery of the universe’s accelerating expansion, driven by some unknown dark energy, has only deepened the mystery.

The 21st century has brought experimental triumphs — gravitational wave detection, precision cosmology, and quantum computing — yet also theoretical crisis. Physics today stands at a strange frontier: we understand more than ever, yet the most fundamental questions remain unanswered.

What is time? Why is there something rather than nothing? Why does mathematics — a product of human thought — describe the universe so well? These are no longer just philosophical musings. They are the edge of physics.

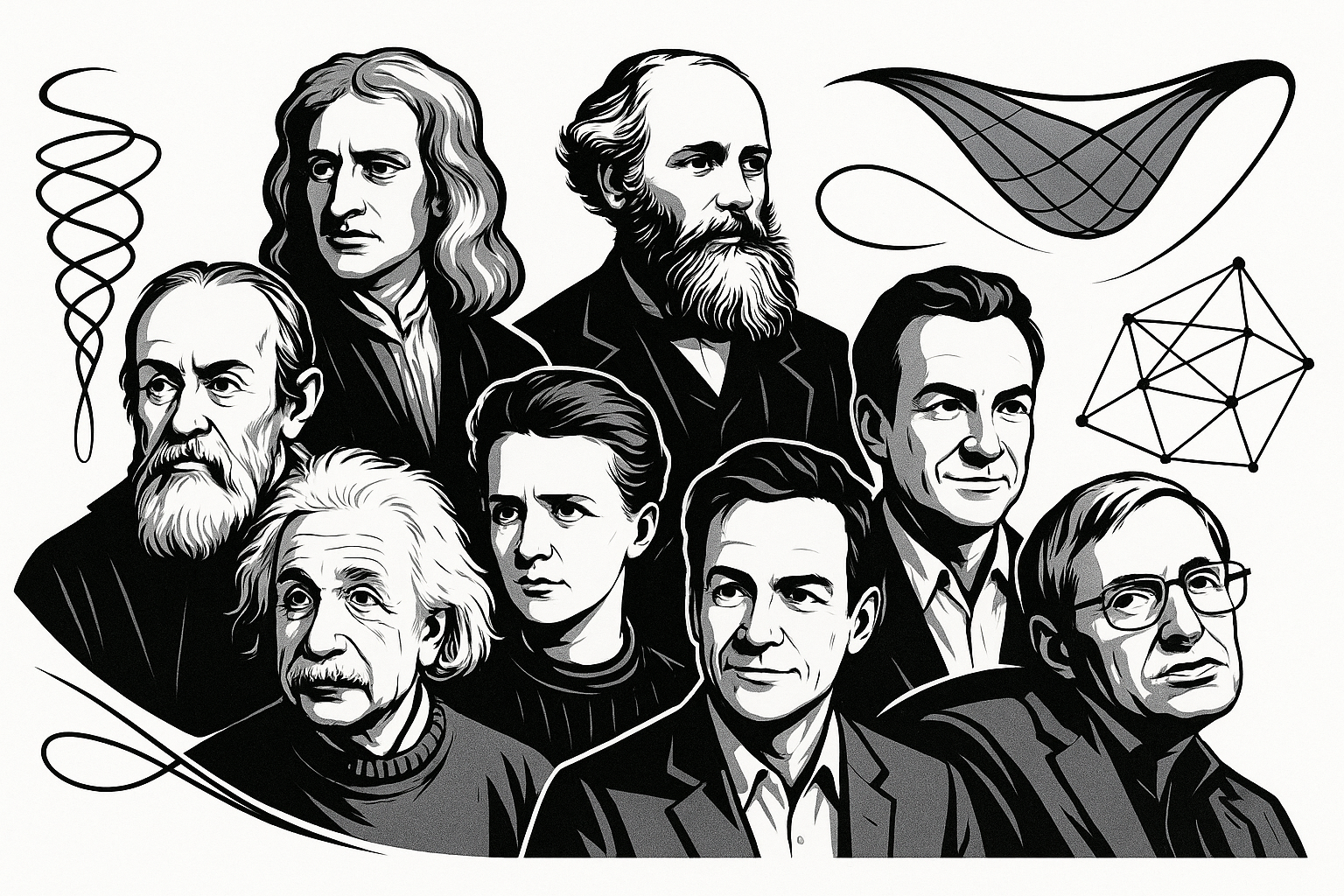

To study physics is to walk in the footsteps of giants — Galileo, Newton, Faraday, Maxwell, Einstein, Planck, Bohr, Heisenberg, Schrödinger, Dirac, Feynman, Hawking — and to continue the quest they began. It is to believe that the universe is knowable, that its rules can be written, and that those rules matter.

This project — Open Physics Notes — is a continuation of that tradition. It is an invitation to journey through the most profound ideas ever conceived. It is not merely a collection of formulas, but a map of the intellectual landscape that defines our reality. It is meant for students, teachers, wanderers, and dreamers — for all who believe that understanding is the first step toward wonder.

Welcome to the most ambitious conversation humanity has ever begun. It’s time to join it.